Losing one's self

Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida and war’s dehumanization of the individual

In a previous series, I read through Shakespeare’s plays and wrote about their significance to the world today. I overlooked one play, Troilus and Cressida. Essays on the other 37 plays can be found in my archives, referenced here for convenience.

When the US and Canada agreed to draw their border along the 49th Parallel North, they stranded a bit of the US hanging off Canadian land. Point Roberts, Washington—where residents must cross two international borders to travel within their state—has previously enjoyed its odd status of being physically joined to a nation of which it’s not a part.

Despite the border, Canadians and Americans alike have called Point Roberts their home, albeit for Canadians, a second home. The residents of Point Roberts considered themselves neighbors to the Canadians who lived nearby in British Columbia, and the Canadians felt the same. Until now.

Trade wars may be unarmed, but they inflict injury nonetheless. Responding to threats from the US President to overtake Canada and impose steep tariffs, Canadians are asserting their sovereignty and self-determination by shunning America and its commerce. Canadian travel to the US is sharply down. Families opted for staycations during the recent school break rather than visit the US, as they would normally do. Shoppers are reading the fine print on labels before making a purchase and learning how to discern whether the provenance is truly Canadian or American.

No US city has felt the impact of ‘Buy Canadian’ so keenly yet as Point Roberts. Its residents are being shunned. They report feeling like they’re going through a divorce. Homes remain shuttered as their former Canadian neighbors take their leisure elsewhere. The residents of Point Roberts now fear what will happen if the trade war continues. This community, entirely dependent upon tourism and vacation revenue, may no longer be economically viable. With their equity sunk into homes and businesses in Point Roberts, how would it be possible for residents to move within their state, across borders to the US, if they can bring themselves to make that decision?

This sudden turn can only bring confusion and a sense of unfairness to the Point Roberts residents. They have done nothing wrong. They were once valued neighbors. They’ve done nothing to deserve being ostracized. They are being treated as objects branded by their nationality, rather than the flesh-and-blood neighbors they were only a few months ago.

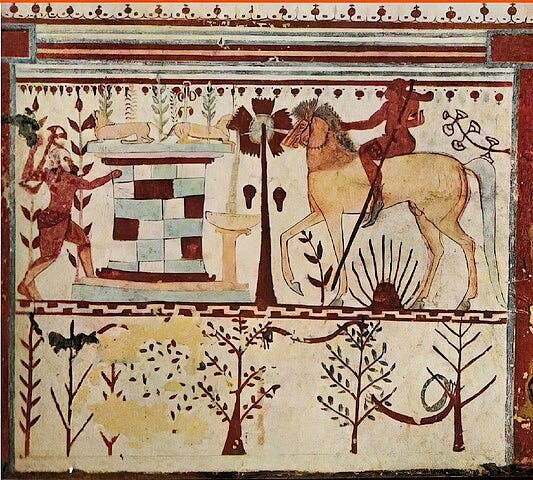

Shakespeare sets Troilus and Cressida in the nexus between a town under siege and the outlying camps of its powerful aggressor. The play uses a love story and a temporary pause in the war to depict the humanity of individual characters: the deeply-felt passions of Troilus, Cressida’s savvy and tempered approach to life, Achilles’ bloated ego and sloth, Ulysses’ strategic and judgmental intellect. Through the course of the play, events erase characters’ humanity as it casts them as extensions of state power.

Most chilling, characters accept the loss of themselves as the people they once were. This is how people become avatars for the state. This is how victims are made.

Synopsis

Shakespeare sets his play in the doldrums of a war, seven years and counting. The Greeks, having brought a war to Troy, are encamped outside the city. Achilles can’t be bothered to leave his tent. Ulysses complains bitterly to their leader, Agamemnon, about the Greek soldiers’ disorganization and insufficient discipline to authority. Even Menelaus, Agamemnon’s brother and the man whose grievances instigated the war, lacks any passion for the cause—which is, at face value, a domestic argument that swelled incommensurate to its injury.

It all started when Menelaus’ wife, Helen (she whose face launched 1,000 ships), become the paramour of Paris, son of Troy’s king, Priam. The Greeks retaliated by mounting an attack against Troy to reclaim Menelaus’ honor and his wife. Long years have passed with many lives lost, and the casus belli seems no longer material to the conflict. Helen is a trivial character, seen only once onstage, teasing Paris’ brother Troilus. The Greeks have lost their sense of purpose in the war, and many spend their time idly.

The Trojans retain their sense of injury—the Greeks brought the war to their city, after all—but Troilus has little interest in the war as the play opens. He’s fallen in love with Cressida and is desperate for her attention. He pleads with her uncle, Pandarus1 to intercede on his behalf. Cressida acts coy when her uncle tries to promote Troilus to her, but she too is smitten. After Pandarus brings them together, he suggests they go to bed together (fulfilling the terms of his name).

As they arise from bed, Cressida is taken away by the Greek Diomedes, and she learns that she’s been exchanged for the release of a Trojan who’d been captured. Cressida’s father had defected to the Greeks, and he’s demanded that Troy yield his daughter to him. Before the two lovers depart, they exchange love tokens: Troilus gives Cressida a sleeve and she gives him a glove.

Hector, son of Priam and brother to Troilus, sends Aeneas to Agamemnon with a challenge for the Greeks to send one man to fight Hector the next day. The Greeks accept the challenge, but who should fight Hector? Achilles seems the logical choice, but Ulysses—who’s the strategist for Agamemnon—sees no upside to this. If he wins, Achilles will take it as a personal accomplishment; if he loses, the entire Greek camp will have to bear the loss. Ulysses decides to ensure that Ajax, a dim-witted bear of a man, is presented to fight Hector. While unsure that Ajax will prevail, Ulysses considers Achilles their backup option.

Troilus follows Cressida as she’s brought to the Greek camp, and he watches from the shadows as she speaks with Diomedes. They appear to be intimate, and Cressida gives Diomedes the sleeve that Troilus had given her. Troilus is enraged by her betrayal.

Hector fights Ajax, but calls off the fight claiming he cannot battle his own family: it turns out that he’s related to Ajax. The challenge ends amicably, and the Greeks host Hector for an evening meal. It’s agreed that Hector will fight Achilles the next day.

As he heads off to the fight, Hector is warned by all of the women in his life—his sister Cassandra, who’s a seer, his wife, and his mother—that the fight will end in his death and the destruction of Troy. He waves away their concerns.

Hector wins the fight with Achilles but lets him live. Later, Achilles finds Hector unarmed. He orders the Myrmidons (his private security detail) to kill Hector, which they do. Achilles takes credit for killing Hector, and the war starts anew. At the end of the play, the Trojans mourn Hector’s ignoble death and Achilles’ desecration of the corpse, tied to a horse tail and dragged through the muddy field.

Troilus has found his purpose.

TROILUS No space of earth shall sunder our two hates. I’ll haunt thee like a wicked conscience still, That mouldeth goblins swift as frenzy’s thoughts. Strike a free march! To Troy with comfort go: Hope of revenge shall hide our inward woe. [Exeunt marching]

Layers of identity

The questioning of who people are runs thematically through the play.

In the first scene, Troilus speaks with Pandarus, who compares his niece to Helen. Troilus is put out with him: how does this advance his suit for her?

TROILUS

Tell me, Apollo, for thy Daphne’s love,

What Cressid is, what Pandar, and what we?

-Act 1 Scene 1

In the following scene, Pandarus tries to entice Cressida to make a match with Troilus. He enters as she and her servant Alexander watch a parade of Trojan soldiers below in the street. Cressida opens the scene by asking Alexander who’s passing by, and what they’re doing. Each man is identified by name.

Cressida is admiring Hector as her uncle enters. Pandarus nudges Cressida to compare Hector and Troilus.

CRESSIDA What, is he angry too?

PANDARUS Who, Troilus? Troilus is the better man of the two.

CRESSIDA

O Jupiter! There’s no comparison.

PANDARUS What, not between Troilus and Hector? Do

You know a man if you see him?

CRESSIDA

Ay, if I ever saw him before and knew him.

PANDARUS Well, I say Troilus is Troilus.

CRESSIDA

Then you say as I say, for I am sure

He is not Hector.

PANDARUS No, nor Hector is not Troilus, in some degrees.

CRESSIDA

‘Tis just to each of them: he is himself.

PANDARUS Himself? Alas, poor Troilus, I would he were.

-Act 1 Scene 2

Together they watch the continuing parade of Trojan warriors, identifying each of them as they pass by and commenting on their qualities.

In the next scene, Aeneas arrives at the Greek camp with a message for Agamemnon sent from Hector. Aeneas, a Trojan, can’t identify Agamemnon by sight. He asks to speak directly to him, and asks where he may find him. Agamemnon plays him along, refusing to state his name, until he slyly acknowledges his identity.

The play is shot through with characters asking who they’re talking to and announcing their identities. Hector calls off his fight with Ajax, having already commenced it, recognizing their kinship. The sides aren’t neatly divided: Greeks live in Troy and Trojans live amongst the Greeks. The war began with Helen leaving Sparta to live with Paris in Troy. Despite the long-waged war, who the combatants are as individuals remains unclear on each side.

To say one is a Greek is to adopt an artificial identity. Suppose Helen was not a mythical character. She would come into the world as Helen, daughter to parents, related to their families. She would also be herself, a unique identity known best to her alone. The nation or city where she lived would give her a civic identity. Should she marry, that union would lacquer on another layer of her identity. The mythic Helen’s identity changed additionally as she left Sparta to marry Paris; her renown created ideas of her beyond her control. Who is this women, then?

Almost none of the men fighting the Trojan war had a personal stake in whether Helen was sent back to Menelaus or stayed in Troy. They were called upon to fight for their side based on their civic (and for some, familial) identities. Hector acknowledges this in Act 2, as he tries to use reason to understand how just their fight is. He considers the right of owners to their property, an idea he applies to wives.

HECTOR

If Helen then be wife to Sparta’s king,

As it is known she is, these moral laws

Of nature and of nations speak aloud

To have her back returned. Thus to persist

In doing wrong extenuates not wrong,

But makes it much more heavy.

-Act 2 Scene 2

Despite the logic that would send Helen back to Sparta, Hector decides that Helen should remain, “For ‘tis a cause that hath no mean dependence / Upon our joint and several dignities.” Troilus’ opinion is that Troy fights not for a woman (“I would not wish a drop of Trojan blood / Spent more in her defence.”), but for the glory of defeating the Greeks who waged war on them.

TROILUS

She is a theme of honour and renown,

A spur to valiant and magnanimous deeds,

Whose present courage may beat down our foes,

And fame in time to come canonize us—

-Act 2 Scene 2

Cressida’s character changes remarkably during the events of play, beginning as a woman with agency and devolving into an object moved about by men. In Act 1, she knows her own mind and she employs it to foil efforts by Troilus and Pandarus to know what she’s thinking. She takes Troilus as a lover, and spars with him as an equal in their courting. She resists being taken to her father, in the Greek camps: “I will not, uncle, I have forgot my father. / I know no touch of consanguinity, / No kin, no love, no blood, no soul, so near me / As the sweet Troilus.” (Act 4 Scene 5).

When she’s taken away, she pledges she’ll be true to Troilus, but he isn’t certain she will be able.

TROILUS

No, but something may be done that we will not,

And sometimes we are devils to ourselves,

When we will tempt the frailty of our powers,

Presuming on their changeful potency.

-Act 4 Scene 5

Indeed, Cressida’s fate is no longer in her hands once she is captured. When Diomedes brings Cressida to Agamemnon’s camp, the Greeks pass her around from one man to the next, each kissing her. Diomedes lays claim to Cressida, and in the end she accepts her fate. In a monologue, she explains the change in her behavior:

CRESSIDA

Troilus, farewell. One eye yet looks on thee,

But with my heart the other eye doth see.

Ah, poor our sex! This fault in us I find:

The error of our eye directs our mind.

What error leads must err. O then conclude:

Minds swayed by eyes are full of turpitude.

-Act 5 Scene 2

Troilus, watching from the shadows, calls her a whore, just as Ulysses had done when the Greeks had passed her around the camp. This, Troilus tells Ulysses, is not his Cressida: “No, this is Diomed’s Cressid. […] This is and is not Cressid.” From his perspective, women’s identities are defined by how men see them. Troilus’ Cressida is faithful to him; Diomedes’ Cressida is a whore.

Cressida claims her eye was drawn to Diomedes. It’s fair to ask, since the male characters have compared women throughout the play: compared to whom? Cressida’s been captured and taken to live in an enemy camp, where she was passed around amongst the men. She’s left with only one viable option, to accept being the mistress of one man rather than handed around to many. Diomedes, although brutish, is mollified by her acquiescence. She adopts another identity to survive.

Transformation into an object of the state

The title of the play suggests it will be the story of two lovers whose affair has tragic consequences, like Romeo and Juliet, or Antony and Cleopatra. The play undermines that expectation. When warring factions rip them apart, the title characters adapt to their changing circumstances. The tragedy that ends the play isn’t the demise of Cressida but of Hector. Troilus’ final cry for revenge has nothing to do with his lost love, but rather to rally Trojans to fight against their aggressors to save Troy.

The title characters alone undergo transformation through the arc of the play. Cressida, her freedom lost, becomes subservient to the will of her captor. Troilus, initially enthralled with love and with no interest in war, becomes a warrior—as we might say today, an incel radicalized to a cause. He remains a free man, but is he? Watching Cressida’s betrayal with Diomedes, Troilus had to be restrained from acting on his heightened emotions. By the end of the play, Troilus has given himself over to his passionate response to Hector’s death.

The story, seen from this perspective, highlights how people can be induced into fighting and acquiescence by manipulating their emotions and their circumstances.

Learning about WWII, I used to wonder how Germany could find so many men and women willing to execute its crimes against humanity. This week, I’m asking the same about the employees who work in privately owned facilities that imprison immigration detainees cruelly.2 The state must rewire minds to accept that the state’s cause is just, regardless what their senses tell them. They must dismiss the humanity of others as well as their own, and recognize only the identities assigned by the state. That identity based on civic association, one’s nationality, is all that matters. From this the aggressor derives solidarity within a community of like-branded souls. From it comes a feeling of ‘orgulous’ superiority3:

In Troy there lies the scene. From isles of Greece The princes orgulous, their high blood chafed, Have to the port of Athens sent their ships Fraught with the ministers and instruments Of cruel war. Sixty and nine, that wore Their crownets regal, from th’ Athenian bay Put forth toward Phrygia, and their vow is made To ransack Troy, within whose strong immures The ravished Helen, Menelaus’ queen, With wanton Paris sleeps; and that’s the quarrel. -Prologue

I stand with those protecting Canadian sovereignty by voting with their (Canadian) dollars. I’m also sympathetic to the residents of Point Roberts, who find themselves trapped by a cartographical quirk between two warring nations. Their quarrel is not with their neighbors. It’s with the instigator of this cruel war.

Ellie’s Corner

Today was her spa day; she’s smelling especially good to me. No doubt, she’s unhappy she doesn’t have that eau de chienne that’s her personal parfum.

She’s still a good dog, everyone.

Thanks for reading,

Pandarus gives us the verb pander, to procure women or services for others. The play’s text gives a little etymological lesson on this, just in case you didn’t know.

The Guardian article linked above and here is a first-person account of a Canadian woman who was detained in the US for two weeks. The conditions forced upon the detainees are brutal enough; the callous treatment by guards and staff impose a psychological cruelty that’s inexcusable.

Orgulous means haughty.

This is a really good articulation of how self-definition (self-selection) can drive ethical and moral behaviors. "Who" each one of us is, is itself always determined by context to some extent. It goes to the fact that we are social creatures always in socially determined contexts.