Every literate person is able to write, but identifying as a writer communicates more than knowing how to read and write. The self-proclaimed writer states not just their activity nor how they earn income: they’re claiming an identity.

Whether bold enough to make the claim, you know you’re a writer if you’re compelled to translate sensation into words that exist outside you. You’re a writer if you’re driven to put words on a page. Still, you may be shy about calling yourself a writer if your writing hasn’t been accepted by the publishing gatekeepers.

Was Emily Dickinson a poet when she was alive, despite the fact that only ten of her poems were published? Or did she become a poet only posthumously, when hundreds of her poems were published? How many Dickinsons have never breached the gates of publishing, but have written obsessively out of creative need? Would we call them writers? Would they dare to claim they were?

I’m publishing this piece using a service that’s attracted thousands who put their thoughts into written words. Although few of these writers are household names, the platform hosts many professional writers whose work generates income. Many more who publish here may not present themselves as writers in their daily lives. I don’t call myself a writer, although I write and self-publish. My wariness is inextricable from thinking of art as a profession, rather than as an extension of the human condition.

This was on my mind as I wrapped up my Shakespeare project and considered where to go next. I thought about writers who’d been denied at publishing’s gate and writers whose work addressed their exclusion. I also became intensely interested in hearing voices with a different pitch. Female voices.

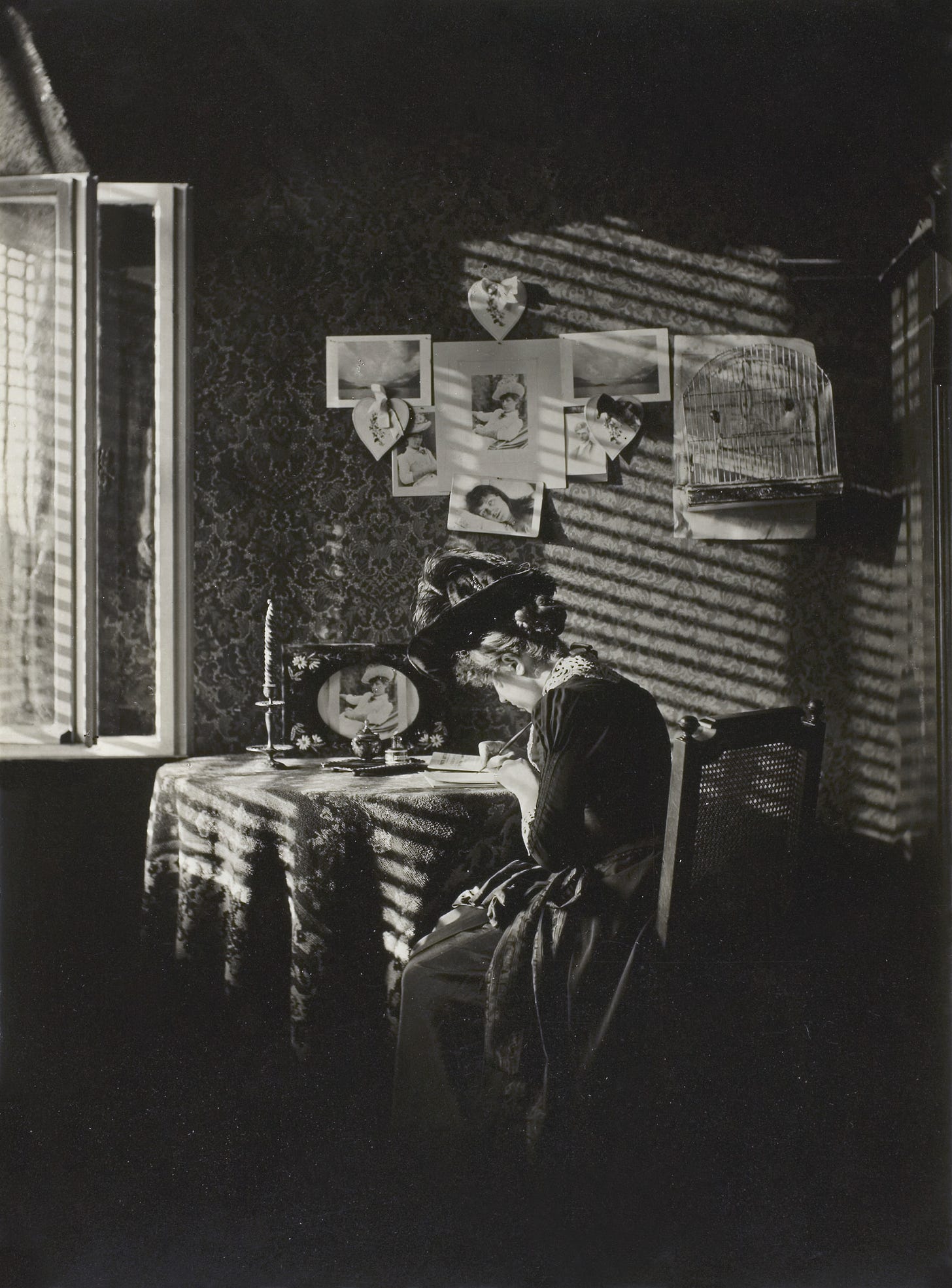

Women have been writing creatively as long as people have been writing; women are people after all. If they weren’t born to leisure and yet were fortunate to have acquired literacy, they wrote when they could, wedging it in between the daily tasks that family care and labor required. Those born to wealth may have had the luxury of unclaimed time, but may not have had greater access to distribute their work. Regardless the challenges, women wrote for the same reason men have—because they felt compelled.

And so, a project is born.

The ‘Shut Out, Not Shut Up’ project

My objective is to discover works written by women through history. More than identifying the stories of women writers through history, I want to read what they wrote and understand how they viewed their worlds.

I’m starting with only a freehand sketch in my mind. Because it’s a journey of discovery, the work won’t be governed by a chronological order. These guidelines will keep me on track:

I’m not an historian and this isn’t a scholarly expedition; it’s a project of discovery. I won’t be comprehensive. I don’t intend to be dry and pedantic. I’ll be looking for vibrant works that spark imagination.

The selected works must be accessible to most readers, meaning in print or online. This, understandably, limits many early texts.

My audience and I need to be able to read the texts, so the work or its translation must be in English. You may have fluency in many other languages, but since I write in English, I’m assuming that this language is our common denominator.

This project has no political agenda other than to amplify other women’s voices. Sometimes those voices will be political. That’s OK. Women are allowed to have points of view.

Classical literature in the Western tradition articulates a sliver of human existence—that which has been lived by privileged men in Europe and the US. Literature has also been written by mothers, laborers, and unmarried women wherever they were born. Some of them assumed a male pen name to gain access to publishers and therefore to an audience. All were shut out in their female identity. But none of them shut up.

Let’s hear what they have to say.

Ellie’s Corner

Ellie has something to say.

Thanks for reading,