Note: This is the first in a series of posts exploring our world through the works of Shakespeare. I hope to work my way through the entire list of 37 plays, but let’s take it one play at a time. I’m ordering the plays using the timeline provided by the Royal Shakespeare Company.

Don’t believe your eyes

The Washington Post reported on a truly disturbing story, in which the images of children lost to their families are made to appear alive through the use of AI:

Now, some content creators are using artificial intelligence to recreate the likeness of these deceased or missing children, giving them “voices” to narrate the disturbing details of what happened to them.

In one video, an AI-generated version of a 2-year old child introduces himself before stating that ‘he’ would be alive if only his mother hadn’t made one slight error. The (actual) child had been abducted by two 10-year olds who tortured and killed him. His mother had once said she blamed herself for turning the wrong way while in pursuit and failed to see the abductors.

This is cruel beyond imagination, and it is false in so many ways. The image may be based on images of the child, but it is not the child, and it would never be alive. We live, however, in a post-truth world. Although TikTok removed this content,

TikTok’s guidelines say the advancement of AI “can make it more difficult to distinguish between fact and fiction, carrying both societal and individual risks

Navigating a world in which the true is condemned as counterfeit and the false is venerated as truth is not new to our times, although its pervasiveness can rock you on your heels. The world was once enlightened, its leaders using reason to determine the answers to big questions. Today’s world is one in which almost half the population of the US favors belief in falsehoods over the facts they see with their own eyes. It is a world in which high-placed tricksters manipulate what their marks believe.

This is the world dramatized by “The Taming of the Shrew”.

Actual or counterfeit?

Shakespeare often played with the motif of counterfeits, which he sometimes attributed to the essential nature of theatre, which is to dissemble (all the world’s a stage). This play, however, is relentless in its use of this motif.

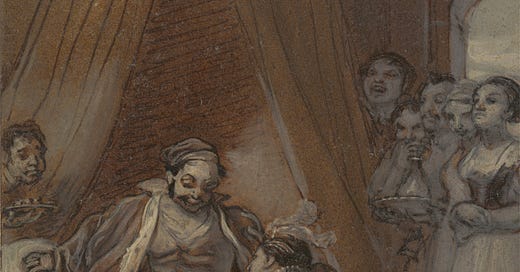

In the play’s framing device, a wealthy Lord constructs an elaborate ruse to dupe Christopher Sly, a lowly drunkard. Sly wakes up in a fancy bed in the Lord’s mansion. Initially suspicious, Sly soon decides to go along with the fiction that he’s a rich man who’s been unconscious for fifteen years, with a wife (who is actually a male page), servants, and riches beyond his dreams. Before he can bed his ‘wife’, he’s encouraged to watch a play (a group of players having stop by the mansion to perform, in timely fashion). The Lord, Sly, and the other players in the ruse settle in above the stage, as the play begins in earnest.

Synopsis

Baptista Minola is a rich man living in Padua with two daughters: Katherina, the older, and Bianca. Both young women are beautiful and spirited. They trust in their father’s support and benevolence, and confidently expect to make their own decisions in life. Although both are unmarried, they trust that they’ll be able to choose their husbands. Katherina suffers no fools, and unfortunately for her, her home in Padua is beset by foolish men. She has no patience for them, and speaks her mind freely. The foolish men write her off as a shrew.

Baptista announces to the male suitors for Bianca that Katherina must marry before the younger Bianca can wed. Meanwhile, he wants Bianca to continue her education, so he exhorts the suitors to bring him qualified tutors for her. The suitors plot how to use the guise of a tutor to get close to Bianca, and how to find a gull to marry Katherina, to clear the way for them to pursue Bianca’s hand.

Two travelers arrive in Padua with their servants.

One is Lucentio, who watches Baptista set the ground rules for his daughters’ marriages. While he’s watching this scene he falls in love with Bianca. Lucentio concocts a wild scheme in which he and his servant switch identities: this scheme grows more complex the deeper they get into the story, because falsehoods tend to snowball, forcing ever more outrageous lies.

The other traveler is Petruchio, a man who recently inherited a great deal of wealth from his father. Petruchio only cares for money, and quickly announces his intentions to enhance his wealth through marriage. He’s accompanied by Grumio, a servant with a caustic wit, and a character well known in Elizabethan theatre as the fool (jester) who speaks truth to power. Grumio will serve as the only effective commenter on Petruchio’s single-minded avarice.

To the foolish suitors’ delight, Petruchio relishes the idea of marrying the ‘shrewish’ Katherina. This, they think, clears their path to claiming Bianca for themselves.

The foolish suitors end up being no match for Lucentio, who wins Bianca’s hand by winning over her mind. Petruchio takes the opposite route with Katherina. Once he has Baptista’s agreement on her dowry, he abuses Katherina, whom he insists on calling Kate to demean her. He arrives unkempt and surly on their wedding day, forces her to walk from Padua to his home in Verona after the wedding, prevents her from eating or sleeping, shows her new clothing then takes it away. He congratulates himself for his cleverness in taming his shrew. One of the foolish suitors takes appreciative note of Petruchio’s methods for his own use, should he gain a wife in a local widow.

En route while returning to Padua for Bianca’s wedding, Petruchio forces Katherina to make false statements as if they are true: claim it’s the sun when it is the moon, or the moon after she has declared it the sun. She performs for him. She is, by Petruchio’s measure, now broken, and can be treated like an animal (although, pointedly, not as well as the Lord treated his hounds in the framing set).

The various counterfeits are resolved in the final act, and Lucentio and Bianca are married. The foolish suitor has married the widow, and the widow taunts Katherina at the feast: everyone can now have a go at Kate, since she’s been subdued.

After the meal, the women retire to another room. Petruchio places a bet with the other newly married men: each will send a message to his wife, and the man whose wife responds most quickly wins the bet. Bianca and the widow are both no-shows: they have no intention of serving at the beck and call of their husbands. Katherina, of course, arrives as bidden, and Petruchio basks in winning the bet and having ‘tamed’ his wife.

Just who is being played?

Shakespeare gives Katherina an extensive final speech in which she chides the widow (albeit now remarried) to be kind to her husband, and treat him as ‘thy lord, thy life, thy keeper, / Thy head, thy sovereign’. She really lays it on, ending with a call for extreme abasement, placing her hand beneath his foot: “My hand is ready; may it do him ease.”

On its face, this is a woman manipulated and coerced into abject obedience, and since the play ends soon after, it would be easy to read it this way.

If this is the intention, the play doesn’t quite work. In this play and others, Shakespeare treats with respect women who are educated and use their wits to best men. Characters who are bullies generally find their comeuppance by the end of the play. In this play, every scene puts Petruchio’s bullying on display. He’s unlikeable (his servants only obey him out of fear) and unredeemable.

Baptista has raised his daughters to be educated and to make their own choices (with the provision that they marry wealthy men). And yet, he appears to have allowed his oldest daughter to be abused into a Stockholm syndrome nightmare of a marriage.

But, why should we take Katherina at face value in this scene, when we’ve been shown in every other scene that no one and nothing is what it seems. Characters are stunned, not trusting their eyes, as they’re confronted with false versions of Lucentio and father sharing the stage with their true versions. What if, in this speech, Katherina is saying ‘it is the sun’ while she looks at the moon? What if you aren’t to trust anything she says? This reading rings truer to the overall play, and it makes a greater point about how it is possible to gaslight others into believing a counterfeit reality.

A play for our times

Beyond the London theatre world in the late 16th century, survival in England often required dissemblance. Shakespeare’s parents were Catholic in a time when owning a Catholic Bible was considered treasonous. A relative of Shakespeare’s had been convicted and executed for a plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I, and Shakespeare and his family had ties to several men involved in the Gunpowder Plot. He learned how to navigate through treacherous times.

Yet in many plays, and certainly in this one, Shakespeare goes beyond acknowledging that falsehoods are often clothed to appear true. He advocates for unmasking what is counterfeit and bringing truth to light, even at the risk of death. Katherine’s truth isn’t to be a servant, just as Sly’s truth isn’t to be a lord. To survive, she must play a part, and play it well. For now.

We live in a time of rampant deception. Know your truth. Unmask the deceivers. Survive.

Thanks for reading,

Thanks for sharing.

Avarice. Not a word heard often enough, despite its daily impertinent display. Not knocking money or wealth, but our society certainly seems to have developed an unhealthy relationship with it.

Your Shakespeare revival is also timely. Look at Florida for instance. Yet another, literally, cartoonish effort to short sheet (in an unfunny way) an already anorexic public school system. Apparently proletariat Walmart and Tyson chicken laborers are a threat if taught to think outside the box. US history curriculum, especially pertaining to race relations, begins with Different Strokes and the Fresh Prince of Bel Air. English Literature, especially Sir William…better be a version of G rated Bible Phonics, with pretty pictures and Snow White Tinker-bell language. Although, WTF…even the “purity”of the House of Mouse is questionable if you ask immaculate conception-nyte and intact hymen, Mrs. Guvnah Rhonda Santis.

It’s sad to watch.

Though if I am honest, English Lit (Shakespeare in particular) and Chemistry were my least favorite subjects in high school, pretty sure my grades prove that. But I appreciated and still do appreciate Shakespeare. An open mind. Also, I was blessed to attend high school in London England where Sir William literally came to life on stage for me. I remember my most indelible-upon-the-memory English Lit teacher the late Don Jesse with much bombastic energy saying,

“hell class, we’ll read later…before lunch today you will have seen the writing come to life! Now get on the bloody tube, meet you at the Covent Garden stop in 45 minutes!”

I digress. I am going to voraciously read your Shakespeare essays, cause we all should.

Thank you.

Peace

☮️🇺🇸☯️

PS - I may post an essay of my own dovetailing off yours. I hope that’s okay. It brought back fond memories of my time in London. Plus GiGi reminded me when we were in London (2017) we saw an outdoor theatre on the Thames performance of “The Taming”. There may even be pictures.