Educating women: still radical after all these years

Mary Wollstonecraft’s “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman” argues passionately for rights based on a public and egalitarian education system. We’re still making that argument today.

This essay is part of a series called “Shut Out, Not Shut Up” on women through the ages who’ve written despite being dismissed because of their sex. They persisted.

Previous essays in the series are here.

Commencement speeches typically accomplish two things and occasionally succeed in one more: congratulate the graduating class for their achievement, welcome them to careers that await, and—the distinguishing feature of notable speeches—inspire them to use their knowledge to craft fully realized lives. Here are a few examples.

Steve Jobs (Stanford, 2005)

"Your time is limited, so don't waste it living someone else's life. Don't be trapped by dogma — which is living with the results of other people's thinking. Don't let the noise of others' opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition.”

John F. Kennedy (American University, 1963)

“No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings. Man's reason and spirit have often solved the seemingly unsolvable — and we believe they can do it again."

Barbara Kingsolver (Duke, 2008)

"The arc of history is longer than human vision. It bends. We abolished slavery, we granted universal suffrage. We have done hard things before. And every time it took a terrible fight between people who could not imagine changing the rules, and those who said, 'We already did. We have made the world new.' The hardest part will be to convince yourself of the possibilities, and hang on."

Admiral William H. McRaven (University of Texas, 2014)

“If you make your bed every morning you will have accomplished the first task of the day. It will give you a small sense of pride, and it will encourage you to do another task and another and another. By the end of the day, that one task completed will have turned into many tasks completed. Making your bed will also reinforce the fact that little things in life matter. If you can't do the little things right, you will never do the big things right.”

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (Williams, 2017)

“Standing for social justice must invariably require acknowledging privilege. And I don’t mean that common expression in colleges, “check your privilege,” which to me feels a bit too easy, a bit too simple, bordering on glib. In thinking about privilege, it helps me to use my own experience. I am black (in case you didn’t notice), and I am a woman. And while I am very happily both, and would not change either for anything in the world, these are not identity groups that are privileged. But I do belong to another group that is privileged, and that is class. It means that because I grew up in a middle-class household and I had the good fortune of a good education in Nigeria because of the family I was born into, and because I have since acquired certain degrees, the world extends courtesies to me that it does not extend to people who do not have these qualities. How does this blind me? What am I unable to see because my own experience lies like a shroud around my eyes? If you are a white woman, you are privileged because you are white. In what ways does this blind you to the experience of women who are not white? If you are a student of color, there are many ways in which you are not privileged. But if you are graduating today, there is one way in which you now are. You have a fancy-pants degree. It means a certain kind of access. It means you have something that a majority of Americans do not have.”

Every one of these speeches addressed the graduating class as a whole: everyone has a bed that needs making when they rise, everyone can work on entrenched problems that need solving, every graduate—regardless of identity—shares in privilege that needs acknowledging. Most graduates won’t follow the career paths of their commencement speakers, but all can aspire to incorporate their wisdom, distilled from lives filled with adversity as well as accomplishment. This is the best kind of commencement speech, one that sends mortarboard caps sailing with joy.

And then, there’s Harrison Butker’s speech recently at Benedictine College1.

Barely finishing the perfunctory thanks to his hosts, Butker turns sharply into politics. He criticizes ‘bad leaders’ (whom he later identifies as overly-political bishops) and pointedly targets the President of the United States, criticising Joe Biden on his practice of the Catholic faith.

The speech returns repeatedly to Covid, as if we were still living in lock down, forced to wear masks, and receive vaccinations. Although the Covid remarks may seem anachronistic, Butker’s disingenuous outrage merely signals to his tribe, for whom science is apostasy.

Since I was raised Catholic, I found even more odd a comment Butker made while promoting the Catholic Church. He criticizes priests who are “overly familiar” with the people in their care, perhaps unconsciously raising the spectre of the Church’s adjudicated culpability in the molestations of thousands of children who were indeed in the care of ‘overly familiar’ priests.

A strange commencement speech, you might think. Then Butker kicks the ball he’s placed, addressing only the ‘ladies’ in the audience.

“For the ladies present today, congratulations on an amazing accomplishment. You should be proud of all that you have achieved to this point in your young lives. I want to speak directly to you briefly because I think it is you, the women, who have had the most diabolical lies told to you. How many of you are sitting here now about to cross this stage and are thinking about all the promotions and titles you are going to get in your career? Some of you may go on to lead successful careers in the world, but I would venture to guess that the majority of you are most excited about your marriage and the children you will bring into this world.”

To be fair, he has the humility to say: “Everything I am saying to you is not from a place of wisdom, but rather a place of experience. I am hopeful that these words will be seen as those from a man.”

To this I can say: fair enough. These are thoughts about women from the mind of one man, who feels both the urgency and the privilege to tell women what they think. Many men do the same without acknowledging their lack of wisdom. Perhaps he deserves half a point for that admission, but not enough to put on the board. The speech was no touchdown and he scored no field goal.

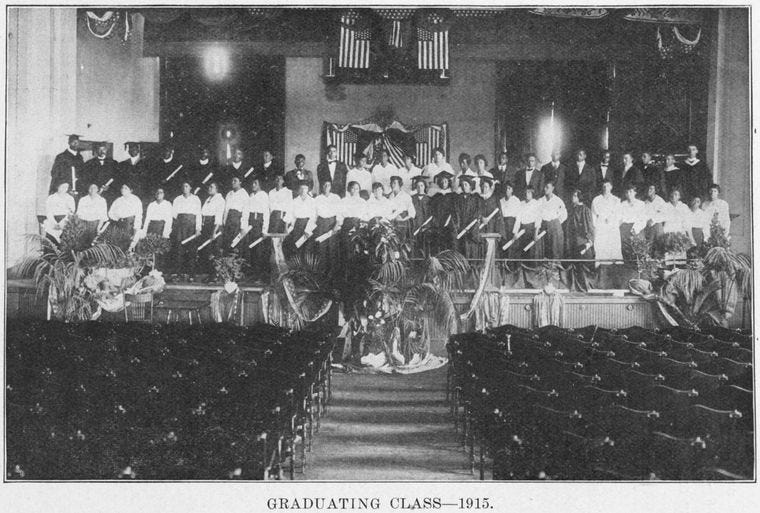

Consider: 101 years after Benedictine College opened its doors to women, its commencement speaker advises its female graduates that their place in the world is in their own homes, their only use to care for a husband and raise children. This speech would be shocking to the first graduating class of 1923. Little wonder his speech lit a fiery backlash.

Democracy, on its graduation during the Enlightenment

In the 18th century, many writers and statesmen looked forward to creating societies that would be improved by implementing ideas born of the Enlightenment. Rousseau, Talleyrand, Madison, Adam Smith: they spoke to their fellow intellectuals as if to a graduating class, clapping them on the back and pointing the way forward to a more just and free society.

It was left to women writers like Mary Wollstonecraft and Olympe de Gouges to question ‘freedom for whom?’ Not for women, assuredly. These women of courage faced head-on the influential men of their times. Wollstonecraft’s 1792 treatise, “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman,” throws down the gauntlet in her “Dedication”:

To

M. Talleyrand-Périgord,

Late Bishop of Autun

The context for her dedication is a 1791 report that the French diplomat Talleyrand had submitted to France’s Constitutional Assembly. The report’s mission was to provide guidance to the Assembly on public education. To be precise, the public education of men.

Wollstonecraft dedicates her work on women’s rights to Talleyrand, offering both an appreciation for his ‘pamphlet’ and to educate him on the rights of women. He aimed too low: national education should serve the entire population rather than a measly sliver of it.

Wollstonecraft wrote “Vindication” in just six weeks, the pages sent flying by the passion of her argument.2 She had a few things on her mind, and she was on fire.

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

Supporting her argument, Mary Wollstonecraft sets two fundamental planks: that there are three qualities elevating humans above other animals: reason, virtue, and knowledge; and the relative physical weakness of women compared to men. The rest of her logic, which I summarise below, follows from these assumptions.

Men have constructed societies based on inequalities (against women, the poor, and the enslaved) to maintain their positions of power. This power dynamic ensures that women remain mostly uneducated and weak, childlike in their dependence on men. When families do educate their daughters, the instruction reinforces a childlike simple-mindedness, training women to be desirable to men for the twenty years they’ll be found useful for their beauty. Without serious education, women’s minds remain vaulted from creativity, critical thinking, and participation in serious discussion.

The harm done is not just to women, but to everyone: men, families, and society. Boys, sent to exclusive schools necessary for career advancement, learn not virtue nor wisdom but how to be brutish to those they think are beneath them. Protected from challenges, their only freedom is to be the worst they can be. They mire themselves as brute creatures, bereft of reason, virtue, and true knowledge.

The little respect paid to chastity in the male world is, I am persuaded, the grand source of many of the physical and moral evils that torment mankind, as well as of the vices and follies that degrade and destroy women; yet at school, boys infallibly lose that decent bashfulness, which might have ripened into modesty, at home.

And what nasty indecent tricks do they not also learn from each other, when a number of them pig together in the same bedchamber, not to speak of the vices, which render the body weak, whilst they effectually prevent the acquisition of any delicacy of mind. The little attention paid to the cultivation of modesty, amongst men, produces great depravity in all the relationships of society….

Wollstonecraft argues that a national education system consisting of day schools that enroll both sexes and all economic classes would solve these entrenched problems.

To render this practicable, day schools, for particular ages, should be established by government, in which boys and girls might be educated together. The school for the younger children, from five to nine years of age, ought to be absolutely free and open to all classes.

She calls for school uniforms and curricula spanning “…botany, mechanics, and astronomy. Reading, writing, arithmetic, natural history, and some simple experiments in natural philosophy […], but these pursuits should never encroach on gymnastic plays in the open air. The elements of religion, history, the history of man, and politics, might also be taught by conversations, in the socratic [sic] form.”

She argues that co-education would prevent debauchery from ruining boys’ constitutions (“which now make men so selfish”), and would prevent the weakening and vanity of girls, which result in their “indolence, and frivolous pursuits”.

She wonders, with these changes, “what advances might not the human mind make?”

Wollstonecraft levels much of her anger at the lost potential she witnesses in women who waste their time on fashion, adornment, and reading sentimental novels. She notes the servitude of women whose work is raising children and earning money to provide them food and housing. However, the real problem isn’t any individual woman, but the system that represses them.

In short, in whatever light I view the subject, reason and experience convince me that the only method of leading women to fulfill their peculiar duties, is to free them from all restraint by allowing them to participate in the inherent rights of mankind.

Calling herself a philosopher, Wollstonecraft builds a phenomenological argument based on experiential data—her own, and what she’s observed in other women. She extrapolates from her life or what she’s witnessed to submit bold generalizations.

Her writings fit the times, not current tastes. Today’s reader, accustomed to writers who must prove their statements using data from external sources, might read Wollstonecraft with a jaded eye. I find myself wanting to prod generalizations to see where their softness makes them yield.

However, to dismiss the whole work on the basis of style would be wrong.

On education for all

I’m the product of a national education system that was free and mandatory for every child in the community: rich or poor, boy or girl, every racial background, able-bodied or not. A child’s religious beliefs (or lack of them) was immaterial to the right to receive a public education. This educational system wasn’t perfect, nor did it solve all of society’s problems. It didn’t ensure equality for all. It didn’t make boys more virtuous or girls more serious.

And yet, that experience doesn’t invalidate Wollstonecraft’s argument. The world I graduated into was more equal for women than the generation before me. I may have attended public school in the US at its apex of achievement—after desegregation, at a time courts oversaw a more equitable distribution of resources, and before the rapid proliferation of private schools and home schooling that constituted the backlash to desegregation. In the years since, political activists have consistently eroded support for educating every child without prejudice.

Decades of exerting a financial stranglehold on public schools have been effective in diminishing the impact of public education. If that had not happened, if politicians instead had been rewarded for educating all of their constituents’ children to expand their horizons beyond their parents’, the country might have realized an expansion of equality and fairness throughout its society. It’s even possible that under such an expansion the deep roots of anti-intellectualism in the US, which today yield the fruits of climate denial and anti-vaccination, might have withered in a soil not nourished by an incessant drip of hatred.

In our current century, two teenage girls, Greta Thunberg of Sweden and Malala Yousafzai of Pakistan, stepped on international stages to advocate for reason, virtue, and knowledge. They personally witnessed both the empowerment of education and the call to action that knowledge brings. They illustrate the inherent truths in Wollstonecraft’s thesis. Education can remove the bondage of ignorance. Once a mind is free, nothing can hold it back.

To those who would oppress, there is nothing more dangerous than an educated woman.

Who is Mary Wollstonecraft?

Born in London in 1759, Mary Wollstonecraft was one of seven children. Her father drank excessively, endangering the family’s financial and physical security. He was abusive, and in response Mary assumed the role of protectress for her mother and sisters. She formed several close relationships with other women and dreamed of building a utopian community for women.

Wollstonecraft, with two sisters, established a school for girls in Newington Green. The school failed, but she put the experience to good use as she developed her singular and innovative philosophy. Living in Newington Green introduced her to a community (the Dissenters, who wanted the state out of religion) that supported her free thinking. She started writing, and with encouragement she began submitting her work for publication.

After her school failed, Wollstonecraft moved to Ireland for work as a governess. She got along well with the children but not so much with her employer, a woman she considered morally and intellectually inferior.3 Returning to England, she incorporated her experiences in Ireland into a novel titled “Mary, A Fiction.” She became friends with her publisher, and through him met leading radical thinkers of the day such as Thomas Paine, Henry Fuseli, William Godwin, and William Blake.

In 1792 she travelled alone to Paris to write. She met an American, Gilbert Imlay, and with him she conceived her daughter Fanny. Her relationship with Imlay deteriorated due to his infidelities, and she returned to England without him. After several attempts at suicide and a trip to Scandinavia, Wollstonecraft returned finally to England. She began an affair with William Godwin and married him in 1797 after she became pregnant. She died of a postpartum infection (puerperal fever) soon after delivering the baby.

Mary was 38 when she died. Her daughter, Mary Godwin, wrote “Frankenstein” and published it under her married name, Mary Shelley.

Reflections on Mary

Education alone can’t account for the courage and vision that mark women like Mary Wollstonecraft and Olympe de Gouges, no more than for modern women like Greta Thunberg and Malala Yousafzai. However, without education we wouldn’t know what these women have to offer the world.

Mary and Malala advocate that universal education is essential to improving society. Innate genius born to a mind caged by misogyny or poverty hasn’t the means to communicate and make itself influential. Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn’s best-selling 2010 book (“Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide”) argues that while talent is universal, opportunity is not. The book quotes a proverb:

“You educate a boy, and you're educating an individual. You educate a girl, and you're educating a village.”

If this is a truth, it’s one in need of perennial reinforcement. Mary Wollstonecraft did her part in 1792 and Kristof and WuDunn contributed theirs in 2010, reaching a far greater audience than an 18th century woman could dream of. Regardless, the state of public education in a ‘first world’ country has declined since 2010, with political activism making increasingly deep incursions into curricula, books, and even sports. This is the true context for Harrison Butker’s commencement speech.

Mary Wollstonecraft lived through periods of want, family abuse, failure, and betrayal by men. She was used abusively, and never experienced extended times of security and peace. With the support of a small group of friends of both sexes, she used her words to strike out against injustice. She confronted some of the most influential male writers of her time.

If you write or make art of any kind, you’ve experienced the soul-wrenching doubt and uncertainty that distinguish the creative life. Mary, and the women who wrote before and after her, wrote as if their lives depended on it. Likely, they did.

Ellie’s Corner

This is the face of someone who knows her rights even if you aren’t cooperating. And she refuses to be denied. Gotta love her.

Thanks for reading,

Harrison Butker’s career is in professional football. He’s a kicker for the Kansas City Chiefs, and occasionally gives commencement speeches despite his modest acknowledgement that he isn’t a professional speaker. His speech travelled far beyond the Benedictine campus this past week, received by a public sharply divided on its content. His defenders have charged that critics haven’t provided sufficient context for his comments to women (the ‘ladies’), so I read the speech and am providing context. You’re free to draw your own conclusions; I’m interested most in the speech’s implications for universal education.

She remarked to a friend about her frenzy in writing it: “the Devil coming for the conclusion of the sheet before it [was] written.” (Editor’s note to the Dover edition of “The Vindication of the Rights of Woman.”)

Source: the Dover Edition of Mary Wollstonecraft’s “The Vindication of the Rights of Woman”, 1996.