Barbie, By Shakespeare

Shakespeare’s “The Winter’s Tale”, plus thoughts about women on pedestals

I’m reading through Shakespeare’s plays in an attempt to make sense of the world. Today I’m writing about “The Winter’s Tale.” For a quick reference to posts on previous plays, click here. Next week, “The Tempest.”

With this play we enter the 4th and last decade of Shakespeare’s plays. After today, only three plays remain in my project plus a final wrap-up. Coming soon: a new project that I hope you’ll enjoy.

You can always count on some women willing to do men’s work in repressing other women. During the convulsive years that belched out the late 20th century’s feminist backlash, Phyllis Schlafly gained more than her 15 minutes of fame selling other women on the perks of their own entrapment. Ira Levin captured the phenomenon in “The Stepford Wives” and Margaret Atwood made it tangible in “The Handmaid’s Tale.” Men can’t hope to have the impact of a woman, a copy of the women she targets, delivering the gospel and admonishing women who resist. It’s both terrifying and ridiculous to witness a woman so ready to betray her sisters.

Terrifying and ridiculous also describe the popular reaction to Senator Katie Britt’s rebuttal of the State of the Union Speech. Presented in an upscale kitchen, Senator Britt introduced herself as a wife, mother, and homemaker. She delivered her lines in a breathy, overly-animated voice (popularly called ‘Fundie Baby’) crafted to promise a compliant woman, religious and yet sexy. Her performance was ludicrous. She holds the title of United States Senator, giving her the same political power as the senior senator from her state, most famous for using his power to block 400 military promotions, some at the highest level.

People laughed, and predictably SNL used Britt’s video for their cold open, which Britt took as flattery. The rebuttal video should have evoked terror.

Individual women achieving a previously unheld summit reliably triggers a tired nod to breaking glass ceilings, which somehow self-heal soon after like some mythic task that must be repeated in perpetuity. Sometimes the backlash is so brutal that the achievement becomes a cautionary tale for other women, but a backlash isn’t necessary: whatever institutional barriers an exceptional person has to overcome aren’t removed with a one-time success.

And, some women desire power for themselves. They rely on men for promotion, fully intending to pull up the ladder behind them. Neither sex has a lock on virtue, and power corrupts. A woman who does the bidding of misogynistic men against other women, in service to herself, is a disgusting spectacle. Using another woman’s suffering to advance one’s own grasp for power should have been a shameful moment for Senator Britt. Instead, she was giddy that Scarlett Johansson played her on SNL.

Greta Gerwig’s “Barbie” presented a different kind of powerful woman. Barbie descends from her solipsistic existence on top of the world to live a real life with all its risks and pain. It’s a remarkable trajectory, from icon to human.

Shakespeare spins The Winter’s Tale as a fantasy filled with entertainment—dancing, japes, humour—and delivering a moral. Barbie comes down from her pedestal, takes a step, her foot flattens, and for the first time it fits naturally the curve of the ground.

This old, wintry tale may surprise you.

Summary

Leontes, king of Sicilia, and Polixenes, king of Bohemia, have been friends since childhood. They are so close they could be brothers.

Polixenes has been visiting Leontes and his wife, Hermione, for nine months (yes, that’s important) and he’s ready to return to his kingdom in Bohemia. Unable to convince his friend to stay, Leontes invites Hermione to use her gifts of persuasion on their guest. Hermione succeeds: Polixenes will extend his stay.

Leontes, although outwardly happy, becomes enraged, convinced that Hermione and Polixenes are having an affair. Leontes prods Camillo, a lord who’s his right hand man, asking what he thinks of Polixenes’ decision. Camillo observes that Hermione’s plea was convincing, but he sees nothing amiss.

Leontes, unable to accept Camillo’s advice, forces Camillo to agree to murder Polixenes. Alarmed, Camillo tells Polixenes of Leontes’ plan. Polixenes and Camillo decide to escape to Bohemia: Camillo is a marked man if he remains in his beloved Sicilia.

Once Leontes learns of Polixenes’ departure, he has Hermione arrested for adultery and treason. He sends a courier to Apollo’s shrine for advice.

Paulina, the wife of the Sicilian lord Antigonus, visits Hermione in prison and learns that Hermione has given birth to a baby girl. Paulina decides to bring the baby to Leontes, thinking that his new baby will soften his attitude toward Hermione.

Leontes, however, is in a mood. He’s grown more convinced of his wife’s unfaithfulness. His son, the very copy of himself, has become ill, and Leontes blames Hermione’s supposed disloyalty for their son’s illness.

Leontes’ attendants try to warn off Paulina, but she persists in bringing the baby to Leontes. Despite the baby looking quite like him, Leontes only sees the stamp of his own jealousy: he orders the baby to be tossed in the fire. Antigonus implores the king, telling him that no lord will undertake this appalling command. Antigonus’ wife Paulina takes a stronger stance against the king.

ANTIGONUS Hang all the husbands

That cannot do that feat, you’ll leave yourself

Hardly one subject.

LEONTES Once more, take her hence.

PAULINA

A most unworthy and unnatural lord

Can do no more.

LEONTES I’ll ha’ thee burnt.

PAULINA I care not.

It is an heretic that makes the fire,

Not she which burns in’t. I’ll not call you tyrant;

But this most cruel usage of your queen—

Not able to produce more accusation

Than your own weak-hinged fancy—something savours

Of tyranny and will ignoble make you,

Yea, scandalous to the world.

-Act 2 Scene 3

Antigonus pledges to take the baby to a distant, deserted place and leave her exposed to die, rather than burn her alive. He takes the baby away.

Hermione is accused in court and she argues her innocence, asking for Apollo to be her judge. The couriers from the shrine read the oracle’s scrolls, which proclaim that Hermione is chaste and Polixenes is blameless. Leontes dismisses this Delphic opinion since it doesn’t confirm his own.

During the trial, news arrives that the prince has died, causing Hermione to fall to the ground. She’s pronounced dead. Using his best post hoc ergo propter hoc illogic, Leontes surmises from these events that he shouldn’t cross Apollo. He asks for Camillo to be recalled and says he’ll reconcile with Polixenes. Paulina rages against Leontes, accusing him of Hermione’s death.

Antigonus brings the baby, called Perdita (‘lost’) to the wilds of Bohemia, where Polixenes is king. He leaves the baby exposed in a terrible storm, leaving with her a casket containing jewels, gold, and her mother’s cloak. As he does, he recalls a recent dream in which Hermione swore that if he leaves her daughter Perdita to die of exposure, he’ll never again see his wife Paulina. He leaves the scene, following the infamous stage direction: “Exit, pursued by a bear.”

An old shepherd and his son, a clown1, find the baby in the storm and take it in. The son tells his father the terrible sights he has just witnessed: a man torn apart and eaten by a bear, and a ship sunk off the coast in the storm.

Time passes. For 16 years, Leontes has lived alone, grieving. Perdita has been raised as a shepherdess, and she’s become close with Polixenes’ son, prince Florizel. Camillo has lived all these years abroad in Bohemia, but he yearns to return to his homeland, Sicilia. Polixenes wants him to stay, Together, they will go in disguise to the shepherd’s home, where Polixenes has heard his son is spending all of his time.

The play introduces a new character, Autolycus, who’s a grifter. He meets the shepherd’s son at market, buying supplies for an upcoming sheep shearing feast. The son presents an easy mark for Autolycus, who steals from him. While conning the son, Autolycus learns about the feast and prepares to make a bigger haul.

Perdita, the Mistress of the Feast, welcomes everyone to the sheep shearing festival. Polixenes and Camillo arrive in disguise. Florizel (Polixenes’ son), who calls himself Doricles at the shepherd’s home, flirts with Perdita and they dance together. Polixenes asks the old shepherd to identify the man dancing with Perdita, and the shepherd replies that he’s Doricles, who’s in love with his daughter Perdita. Polixenes admires Perdita, noting that she appears to be from a higher class than her surroundings suggest.

Autolycus shows up, disguised as a peddler, bringing trinkets and songs to sell. The stage fills with singing and wild dancing.

The old shepherd offers to marry Florizel/Doricles and Perdita. Polixenes steps in and asks Florizel if he’s asked his father for permission to marry. Florizel responds he hasn’t and won’t. The old shepherd urges him to do so, but Florizel resists.

Polixenes removes his disguise to disclose his identity. He refuses Florizel permission to marry Perdita, then loses his temper entirely. He disowns his son, threatens the old shepherd with hanging and Perdita with mutilation. He warns Perdita he’ll kill her if she ever tries to marry his son.

There’s only one remedy for someone targeted by a mad king and that’s escape. Florizel and Perdita decide to flee; Camillo suggests they take a ship to Sicilia. Autolycus steers the old shepherd and his son to the same ship. The play is relocating to Sicilia.

Camillo advises the young couple to present themselves as married when they go to Leontes. He hopes to heal the wounds between the old friends, Leontes and Polixenes, and thus Polixenes and his son Florizel. Autolycus and Florizel exchange clothes and Perdita disguises herself so that they won’t be recognized as they flee for the ship. Camillo returns to tell Polixenes that his son and Perdita have fled to Sicilia, so that Polixenes will follow them there.

In Sicilia, advisors tell Leontes to move on from grieving and re-marry, since having no successors threatens the state’s continuity. Paulina reminds Leontes of his own treachery that left him widowed and without children. She tells him to trust the prophecy: an heir will be found. Leontes, now compliant, swears to Paulina that he will only marry someone she chooses.

News arrives in court that Prince Florizel has arrived, and Florizel and Perdita present themselves to the king. Paulina needles Leontes that his own dead son would have been Florizel’s age, had he lived.

A messenger arrives to announce Polixenes’ approach. Polixenes sends word that his son has married a shepherdess without his permission. Florizel assumes Camillo has betrayed him. He admits to Leontes that he and Perdita are not yet married.

In the streets of Sicilia, Autolycus mingles with gentlemen as news spreads: the king’s heir has been found! Paulina’s steward recounts the evidence: Queen Hermione’s cloak and jewels, along with Perdita’s looks and bearing, have confirmed that she is indeed the lost baby who had been taken into the wilderness. Accompanying this good news is also tragedy—the fateful end of Antigonus, eaten by a bear. Paulina is both stricken to learn of her husband’s gory death and lifted up to witness Perdita’s return.

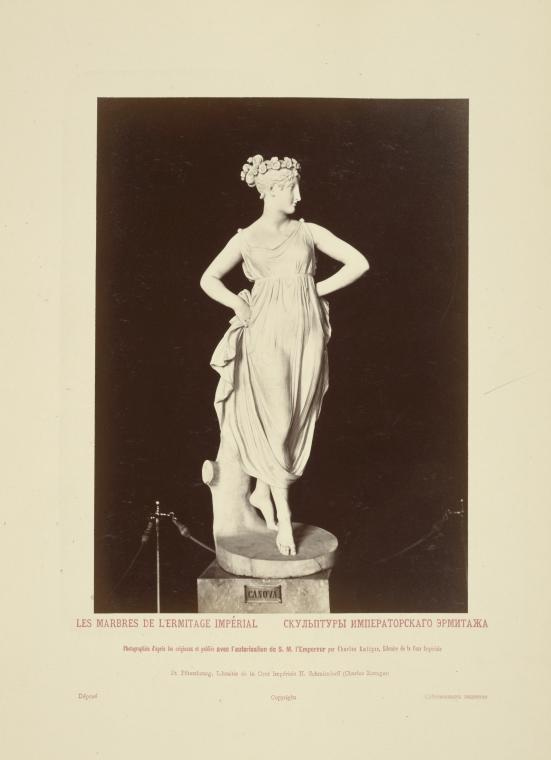

Perdita learns of her mother’s death, and asks to be taken to her statue, one which has been newly crafted in marble by a famous Italian sculptor. Paulina had commissioned the work and she’s had it installed at her place. Leontes and Perdita go there to visit the statue, accompanied by the rest of the cast.

Paulina reveals the statue of Hermione, stunning everyone into silence. Leontes mentions that Hermione appears much older in the statue than she did when he last saw her. Paulina chalks it up to the sculptor’s skill in envisioning Hermione in later life. Perdita asks to kiss the statue, but Paulina resists, claiming the paint is still wet. Seeing that her ruse is getting out of hand, Paulina desperately tries to draw the curtain over the statue, but Leontes insists on kissing it.

Paulina relents. She says she will make the statue move, and indeed Hermione descends, proving she’s human and not statue. She’s reunited with her family. Friends are reconciled. The young couple are to be wed.

LEONTES Good Paulina, Lead us from hence, where we may leisurely Each one demand and answer to his part Performed in this wide gap of time since first We were dissevered. Hastily lead away. Exeunt -Act 5 Scene 3

Thoughts

The curious way in which Perdita is found

Typically, the last act is a dénouement resolving misunderstandings that arose from conflicts. These resolutions establish order from chaos.

We saw this in the previous play, Cymbeline, in which the last act hosted a cascading series of aha! moments for the characters, if not the audience. The last act in The Winter’s Tale departs from that tradition in a striking way.

After bringing most of the characters to Leontes’ court, the play cuts away to a scene in which several anonymous gentlemen are hearing the rumors of what’s just happened with the royal family. They talk about the amazing revelations. They learn that the king and his lost daughter have been rejoined. They listen to the tragic tale of Paulina’s husband being eaten by a bear. They hear about Perdita receiving news of her mother’s death. Through these gentlemen, we learn of Hermione’s statue being commissioned by Paulina and Perdita’s desire to visit it. That’s a huge information dump that would have provided great spectacle if we had seen the actors playing it. Instead, we’re told about it.

Even stranger, Autolycus, the common swindler, is mixed in with this scene. He uses the opportunity, when he spies the old shepherd and his son, to cozy up to them now that they’re semi-related to a Princess and can now be considered gentlemen themselves. It’s a curious interlude that interrupts the crescendo that the dénouement generally builds.

This scene mirrors the earlier scene in Bohemia, in which the most spectacular drama (Antigonus eaten by a bear and the shipwreck) is recounted by the shepherd’s son. Although these events would be a staging nightmare, that they’re told by the artless shepherd’s son is a distinct choice. It dramatizes the creation of a folk tale.

“The Oxford Shakespeare” offers this explanation of the play’s title:

A mid sixteenth-century book classes ‘winter tales’ along with ‘old wives’ tales’; Shakespeare’s title prepared his audiences for a tale of romantic improbability, one to be wondered at rather than believed; and within the play itself characters compare its events to ‘an old tale’.

Much of the sheep shearing festival in Act 4 displays a spectacle of ‘satyrical’ dancing and songs that the commoners have purchased from Autolycus. The play seeks to evoke a mood of being within a winter tale, in which ordinary people carouse and tell tall tales, make merry, and enjoy their good fortune.

The last act’s scene in which the gentlemen share news amongst themselves bursts through the standard device in which the principal characters trade bits of information previously hidden to them, putting together the pieces of a puzzle. The way this play resolves the puzzle reinforces how winter’s tales are told. It re-centers the story from the court and onto the people who, as Lorde sings, “would never be royals."

Leontes’ strange jealousy and Polixenes’ too-quick anger

Mirroring each other in the play’s bookends, Leontes and Polixenes make startling transitions from loving family men to vengeful autocrats. With little noticeable spark, each king transforms rapidly from happy beneficence to mortified offense, moving swiftly to sentence loved ones to banishment or death. The effect is mind-spinning. What’s going on?

In Leontes’ court, Hermione does only what her husband asks her to do: win over his friend to remain as their guest. Hermione, who’s pregnant at the time, has shown only virtue and loyalty. She loves her husband’s friend because her husband loves him. Neither she nor Polixenes say or do anything to cause Leontes to be jealous. And yet, he suddenly and seemingly without provocation turns on her, imprisoning her, banishing the baby she births. Where does this come from?

Key to this scene is Hermione’s appeal to Polixenes. Prompted by her husband to beg a longer visit from their guest, Hermione speaks directly to Polixenes. She doesn’t speak through her husband; she doesn’t triangulate the appeal through her husband. She doesn’t defer.

Leontes’ intention in using his wife on his behalf was to enlarge himself in his friend’s eyes. Here I am, with a beautiful wife who is an extension of myself: I overpower you with my presence and love for you, so you must give in to me. Hermione’s pitch, however, diminishes him. Her speeches move the focus of Polixenes’ attention to herself, away from Leontes. Polixenes’ acceptance of Hermione’s request, after having rejected Leontes’, renders Hermione more powerful than her husband. This, Leontes thinks, is a betrayal.

Without a counterweight, a king experiences no restraint to making mistakes. Camillo hopes to serve as the voice of reason. He tries to soothe Leontes from the flush of jealousy; he attempts to mollify Polixenes’ rage against Florizel. Camillo is kind and supportive, but unfortunately he’s loathe to oppose a king. The two kings, like brothers in their temperaments, lack the means to temper themselves. They need opposition; without it they become tyrants.

Paulina, the heart of the tale

Paulina alone stands up to Leontes, and despite his threats, he yields to her. Paulina is more courageous than her husband, who executes the king’s command even though, distant from him, he could have saved the baby Perdita. Despite his own misgivings, Antigonus leaves the baby to die of exposure. For his diffidence, he’s ravaged by a bear.

His wife, however, is a person willing to stand up to power. Paulina is Greta Thunberg, a teenager who faced down the self-annointed power brokers in Davos:

“Adults keep saying: “We owe it to the young people to give them hope.” But I don’t want your hope. I don’t want you to be hopeful. I want you to panic. I want you to feel the fear I feel every day. And then I want you to act. I want you to act as you would in a crisis. I want you to act as if the house is on fire. Because it is.”

World Economic Forum, Davos, 2019

Paulina is Julia Gillard, former Australian PM, schooling opposition leader Tony Abbott on misogyny:

“If he wants to know what misogyny looks like in modern Australia, he doesn't need a motion in the House of Representatives, he needs a mirror.”

Paulina could be seen in Fani Willis when she faced down her accusers in court:

“I’m not on trial, no matter how hard you try to put me on trial.”

Paulina’s voice is necessary; without it there is no rein on power. She’s not all-powerful—she fails to save her own family—but she discovers power in refusing to accept being controlled.

Down from the pedestal

Growing up, I often heard the anti-feminist argument that women benefit from being placed ‘on pedestals’ by men. The argument went: why risk stepping down from the protection and adoration that a pedestal implies?

I’ve never witnessed this pedestal phenomenon in real life, despite how often misogynists have flogged the metaphor. In my experience, women work relentlessly and receive precious little attention or gratitude. The daily experience for most women isn’t protection but restriction. Misogyny, not feminism, has produced these realities.

And yet the metaphor persists, sidelining women’s autonomy. A US senator is portrayed as a ‘homemaker’ who’s as picture perfect as a celebrity and has the limited agency of the breathy child she mimics. Male lawmakers and justices make medical decisions for women. Medical researchers use male subjects to study women’s medical issues.

A pedestal silences and freezes the subject. It objectifies the sentient human it captures. At the end of the play, Leontes and Perdita expect to find the essence of Hermione captured in cold marble. They anticipate seeing her image perfected: youthful, beautiful, stripped of human complexity. They love the idea of Hermione.

What Paulina presents them is instead a woman of solid flesh, who has aged with time, vulnerable. This is the woman Paulina brings down from the pedestal. The perfect wife and mother fabricated by memory doesn’t exist. Happily, Leontes and Perdita embrace the imperfect woman who descends to embrace them.

Strong women counterpoise strong men. Were this concept embedded in the story of humankind, the world would be remade. This isn’t to say that women are good and men are bad—people are all too human regardless their sex—but rather to draw attention to the necessity of opposition. Power needs opposition. Ego needs humility. And crucially, women need power on their own terms, not derived from the power of men.

Thanks for reading,

‘Clown’ is a way of saying a man who’s easily fooled, not a literal jester or ‘fool’ as jesters are called in Shakespearean plays. I’ll refer to him as the old shepherd’s son, since his name in the play (“Clown”) can conjure images that aren’t intended here.

I had been looking forward to this read. It did not disappoint.